Questions

- You are called to anaesthetise a claustrophobic patient who requires an MRI scan. The patient has a cervical fixation device in place to stabilise a recent C-spine fracture, and the neurosurgeons have requested that it remains in situ until after the scan results.Which of the following factors would most likely mean that an MRI scan is contraindicated?

- The provision of a standard anaesthetic machine in the MRI suite

- The patient having a permanent pacemaker (PPM) in situ

- The patient recalling that he has a foreign body in his eye

- The provision of standard infusion pumps in the MRI suite

- A Halo device for cervical stabilisation

- A 77-year-old man arrived in the intensive care unit 2 hours ago following coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). He has a background of interstitial lung disease and hypertension. He is intubated, ventilated and sedated and on a noradrenaline infusion at 0.05 μg/kg/min. Atrial pacing wires are in situ. You are called to see him as the nurse looking after him thinks the ECG has changed. His blood pressure is 110/80 mmHg and the cardiac index reading on the PiCCO is 1.5 L/min/m2. The readings an hour ago were 130/80 and 2.4 L/min/m2 respectively. His 12-lead ECG is shown in Figure 1.1.What is the most appropriate course of action?

- 1 mg intravenous metoprolol

- 300 mg amiodarone over 30 minutes

- Synchronised DC cardioversion with 100J

- Atrial pacing at 100 beats per minute

- 250 µg intravenous digoxin

- 2You are scheduled to anaesthetise an 80 kg man for aortic valve replacement. He is 73 years old and reports a rash upon administration of penicillin. His skin swab is positive for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) colonisation.Which of the following antibiotic regimens is most appropriate for the patient?

- Flucloxacillin 2 g, gentamicin 120 mg

- Vancomycin 1.5 g, gentamicin 400 mg

- Cefuroxime 1.5g, metronidazole 750 mg

- Co-amoxiclav 1.2 g, linezolid 600 mg

- Clindamycin 900 mg, ciprofloxacin 400 mg

- A 76 year old woman who is spontaneously breathing through a temporary double lumen cuffed tracheostomy tube following a laryngectomy becomes acutely breathless. Help is on its way but despite application of high-flow oxygen, her oxygen saturations are 82% with a respiratory rate of 40 breaths per minute.What is the most appropriate next step in her airway management?

- Deflate the tracheostomy tube cuff

- Remove the inner cannula

- Hand ventilate through the tracheostomy tube

- Position the patient upright

- Remove the tracheostomy tube

- A 28-year-old woman has an Achilles tendon repair under general anaesthesia as a day case. She has a BMI of 32 kg/m2 and is taking the oral contraceptive pill. She will need a below knee plaster cast for 6–8 weeks postoperatively.3What is the best form of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis for her?

- Advice on mobilisation and fluid intake

- Graduated compression stockings and pneumatic compression device on day of surgery

- Graduated compression stockings post discharge for 7 days

- Single dose low molecular weight heparin on day of surgery

- Extended course of low molecular weight heparin post discharge

- A 65-year-old woman is scheduled for an extended abdominal hysterectomy. She is not on any anticoagulants but 2 years ago she developed a blood clot following a total hip replacement. At that time her treatment injections caused a wound haematoma, and she was put on a ‘blood thinning’ infusion for several days. At the end of the treatment she remembers having investigations for low platelets in her blood. These results are unavailable.For immediate perioperative prophylaxis this time the best treatment would be:

- A heparin infusion started 6 hours following surgery if bleeding is controlled

- Treatment dose low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) injection once daily

- Fondaparinux injection once daily

- Low-dose aspirin orally throughout the perioperative period

- A danaparoid infusion

- A 21-year-old woman is undergoing a Le Fort I transverse osteotomy to correct her maxillary retrusion. A nasal tube is used and anaesthesia is maintained by propofol and remifentanil infusions. During the down-fracture, her pulse rate falls to 29 bpm and her blood pressure reads 70/30 mmHg. Her oxygen saturation, end tidal CO2 and airway pressures remain unchanged.What is the most likely cause of her haemodynamic compromise?

- Haemorrhage

- Venous air embolus

- Endotracheal tube damage

- Trigeminocardiac reflex

- Remifentanil

- A 64-year-old man with no previous cardiac or respiratory morbidity is attending for his second treatment of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). After his previous treatment, he had a supraventricular tachycardia with a peak blood pressure of 198/105 mmHg, which resolved spontaneously within 5 minutes. For his anaesthetic he had received propofol 90 mg and suxamethonium 40 mg.What is the most appropriate course of action for this second treatment?

- Perform procedure with defibrillation pads on his chest

- Pre-medicate with oral atenolol

- Use intravenous esmolol during procedure

- Use remifentanil infusion during procedure

- Use sublingual nifedipine during procedure

- 4You are called to see a 65-year-old patient in the surgical ward 3 days following an elective abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. A thoracic epidural catheter is in situ. He is febrile and complains of back pain and lower limb weakness.What would be the most appropriate next step?

- Stop the epidural infusion and contact the neurosurgeon

- Stop the epidural infusion, do regular neurological observations and monitor the epidural catheter site

- Arrange an urgent MRI scan and inform the neurosurgeon

- Stop the epidural infusion and start empirical antibiotics

- Remove the epidural catheter and do a full neurological examination

- A 70 kg, 36-year-old man is scheduled for foot surgery under a regional anaesthetic approach.Which of the following needles would you use to perform a lateral popliteal nerve block?

- 50 mm length, short bevel peripheral nerve block needle

- 50 mm length, long bevel peripheral nerve block needle

- 150 mm length, short bevel peripheral nerve block needle

- 100 mm length, short bevel peripheral nerve block needle

- 100 mm length, long bevel peripheral nerve block needle

- A 28-year-old pedestrian struck by a bus presents to the emergency department. In hospital, he has had a primary survey which reveals an obvious head injury; he also appears to have a fracture to his right arm. His chest appears clear and a FAST scan of the abdomen is negative. Because he had been confused, the emergency medicine registrar has asked you to sedate him for a CT scan of his head. On examination, he grimaces and groans to a deep painful stimulus, but does not open his eyes. He flexes his left arm and leg.The safest option for CT scan would be to:

- Titrate small doses of propofol to effect with continuous monitoring including waveform capnography

- Refuse to give sedative drugs on account of his depressed conscious state, but accompany him to the scanner

- Perform a rapid sequence induction (RSI) with propofol and suxamethonium 1.5 mg/kg, and transfer with a propofol infusion

- Perform a modified RSI with 1.5 mg/kg suxamethonium, after 2 µg/kg fentanyl and propofol and manual in-line stabilisation of the cervical spine

- Fit a Miami J collar and blocks and then perform a modified RSI with 1 mg/kg rocuronium and 3 mg/kg ketamine.

- A 19-year-old man presents to a district general hospital emergency department 8 hours after suffering a penetrating injury to his anterior chest. He has a Glasgow 5coma scale (GCS) of 15, heart rate of 105 beats per minute, blood pressure of 95/50 (MAP 65) mmHg, saturations of 99% on oxygen and a haemoglobin of 105 g/L. Transthoracic echocardiogram shows a haemopericardium for which he requires transfer to a nearby cardiothoracic centre for exploration.What pre-transfer intervention is most appropriate?

- Needle pericardiocentesis

- Intubation and ventilation

- Insertion of a pulmonary artery catheter for cardiac output monitoring

- Insertion of invasive arterial and central venous catheter

- Transfusion of 2 units packed red cells

- A 62-year-old man who sustained an isolated non-penetrating chest injury resulting in lung contusions and rib fractures is on the intensive care unit intubated and ventilated. He has deteriorated over the past 72 hours and now has a Po2:FIO2 ratio (PFR) of 50 mmHg with a FIO2 of 1.0 and a positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) of 5 cmH2O. The investigations suggest he has developed Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS).The most important first intervention is:

- Furosemide bolus of 40 mg intravenously and commence an infusion aiming for a negative fluid balance

- Administer a neuromuscular blocking agent

- Perform a recruitment manoeuvre and incrementally increase the PEEP to above 14 cmH2O

- Adjust the ventilator settings to ensure tidal volumes of 6 mL/kg and a peak pressure of less than 30 cmH2O

- Prone the patient

- A 26-year-old woman with a past medical history of self-harm was found unconscious at home with empty alcohol and amitriptyline bottles on the floor. These had been ingested within half an hour. On arrival to the emergency department her Glasgow coma scale (GCS) was 5 (E1, V1, M3). She was intubated for airway protection. The patient subsequently developed a blood pressure of 80/60 mmHg associated with a heart rate of 150 beats per min, a QRS width of 100 msec and multiple ventricular ectopic beats.The next most important intervention is:

- Nasogastric tube insertion and administration of activated charcoal

- Intravenous crystalloid bolus of 20 mL/kg followed by a noradrenaline infusion to maintain blood pressure

- 500 ml intravenous sodium bicarbonate 1.26% for treatment of a broadened QRS complex

- Lignocaine 2 mg/kg for the management of ventricular ectopic beats

- Lipid emulsion 20% 1.5 mL/kg for intravascular sequestration of tricyclic drug

- 6A 28-year-old woman presents with progressive and ascending motor weakness. She reports a recent history of coryzal symptoms.The following would be an early indicator of the requirement for intubation:

- Respiratory rate > 35 breaths per minute

- PaO2 < 8 kPa

- PaCO2 > 6.5 kPa

- Vital capacity < 15 mL/kg

- Absence of bulbar weakness

- A 70 kg elderly man, awaiting an elective transurethral resection of prostate (TURP), is admitted to the intensive care unit (ITU) with urosepsis. His average urine output over 12 hours is 28 mL/hour.His ITU admission and pre-admission clinic biochemistry profile are shown in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Pre-admission and ITU admission biochemistry profile Pre-admission clinicAdmissionUrea (mmol/L)6.211.2Creatinine (μmol/L)83132Na+ (mmol/L)131129K+ (mmol/L)4.55.1According to the RIFLE criteria, which stage of acute kidney injury does this man fulfill?- Risk

- Injury

- Failure

- Loss

- End-stage renal disease

- A 41-year-old man has been invasively mechanically ventilated for three days due to pancreatitis. He develops pyrexia and increasing oxygen requirements. He is noted to have new left lower zone infiltrates on chest X-ray.Which of the following organisms is most likely to be the cause of his deterioration?

- Escherichia coli

- Methicillin sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA)

- Pseudomonas

- Acinetobacter

- Vancomycin resistant enterococci (VRE)

- 7A 32-year-old primigravid patient with a body mass index (BMI) of 55 is on the labour ward. It is 10 pm; she is currently 7 cm dilated and requesting an epidural. The baby is in the occiput posterior (OP) position. You are unable to palpate her spinous processes. On your third attempt, with difficulty, you perform a lumbar epidural at L3/4 and accidentally cause a dural tap.What is the best line of management in this situation?

- Repeat your attempt at an adjacent lumbar level and use a smaller test dose

- Request help from a colleague to attempt the epidural

- Use the ultrasound to help locate the depth of the epidural space before re-attempting

- Abandon your attempt and institute a remifentanil PCA

- Site a spinal catheter, inform midwife and perform subsequent top-ups yourself

- You are fast bleeped to the emergency department (ED) where a 22-year-old woman who is 28/40 pregnant has presented with a history of seizures for the past 45 minutes. A wedge has been placed under the right side of the patient and large bore intravenous access has been secured. Her blood pressure is 180/110 mmHg, heart rate 154 beats per minute, respiratory rate 24 breaths per minute and an arterial blood gas sample reveals a pH of 7.2 with an elevated lactate. The obstetric registrar is present and suspects this is an eclamptic fit. 4 g of intravenous magnesium sulphate (MgSO4) has been given over 5 minutes and anti-hypertensive medication has been started. The patient is still fitting.What should the next stages of management be?

- Secure airway with endotracheal tube (ETT) and perform emergency Caesarean section in the ED

- Commence MgSO4 infusion at 1 g/hour, secure airway with ETT and perform emergency Caesarean in the ED

- Commence MgSO4 infusion at 1 g/hour, give a further 2 g MgSO4 bolus, secure airway with ETT and continue supportive management

- Give a further 2 g MgSO4 bolus and if no response administer phenytoin 15 mg/kg

- Commence MgSO4 infusion at 1 g/hour, give a further 2 g MgSO4 bolus, secure airway with ETT and perform emergency Caesarean section in the ED

- A 5-day-old boy presents to a local emergency department with a 2-day history of increasing respiratory distress. He is lethargic with a heart rate of 184 beats per minute, a respiratory rate of 68 breaths per minute, a blood pressure of 66/32 mmHg, capillary refill time of 6 seconds, SpO2 96% on air on the right hand, but unrecordable from the other limbs. His axillary temperature is 36.1°C, but his extremities are mottled and feel cool to touch. The chest sounds clear and the heart sounds seem normal with weakly palpable femoral pulses. He was given a bolus of 10 mL/kg of 0.9% saline and broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics. A rapid sequence induction was performed, and the patient intubated and ventilated.8The most appropriate next step in his management is:

- Start prostaglandin E2 intravenous infusion and refer to tertiary centre for possible coarctation of the aorta

- Arrange for an urgent chest X-ray

- Insert a nasogastric tube to decompress the stomach to aid ventilation

- Perform arterial blood gas analysis

- Keep the infant warm with radiant heater

- A 20 kg 5-year-old child was brought to the emergency department of a district general hospital with 15% burns from scalding to neck, chest, abdomen and right upper limb having already received 20 mL/kg (400 mL) Hartmann's and 20 µg/kg intravenous (IV) morphine for analgesia. It is 4 hours since the time of injury. On examination, the child appears comfortable, with a heart rate of 110 beats per minute, blood pressure of 124/82 mmHg, a respiratory rate of 22 breaths per minute and SpO2 of 99% on air.The next most appropriate step in the management of this patient for the next 4 hours is:

- IV Hartmann’s at 110 mL/hour. Refer to tertiary centre for further management

- IV Hartmann’s at 110 mL/hour. Admit for further observation and management

- IV Hartmann’s at 75 mL/hour. Refer to tertiary centre for further management

- Intubate and ventilate. IV Hartmann’s at 110 mL/hour. Refer to tertiary centre for further management

- Give IV antibiotic prophylaxis. IV Hartmann’s at 110 mL/hour. Admit for further observation and management

- A 57-year-old woman presents with a history of severe facial pain that occurs in sudden episodes of a few minutes and only affect her right cheek. It starts with a sharp ’electric shock‘ which then becomes an ache before it abruptly disappears. Treatment with carbamazepine was commenced at 100 mg b.d. this week, and this has provided only modest relief.The most appropriate next step in her treatment is:

- Increase dose of carbamazepine

- Microvascular decompression

- Add amitriptyline

- Add lamotrigine

- Cognitive-behavioural therapy

- You are presented with a 43-year-old woman who had a mastectomy 7 years ago, followed by neoadjuvant radiothearpy and chemotherapy for left sided breast cancer. She is currently taking hormonal therapy and has had pain over the left chest wall for the past 2 years.9Which of the following is most correct regarding this patient’s chest wall pain?

- Urgent referral for investigation of recurrence is needed

- Phantom pain is rare in post-mastectomy patients

- Long-term opioids should be commenced

- Brachial plexus pathology is the likely cause

- The pain will usually respond to anticonvulsants

- A 46-year-old right-handed violinist presents with a 3-month history of worsening severe pain in his right wrist, which commenced suddenly after a long performance in a concert. He has noticed the painful wrist going pale and cold at times, and swelling occasionally. Sometimes it sweats, and it has become stiff and difficult to use. It appears smaller than his left hand, and the nails of his right fingers have become brittle and discoloured. He admits to being very distressed and anxious as he is no longer able to perform. Treatment with paracetamol and amitriptyline has been commenced.The most appropriate next step in his management is:

- Pregabalin 75 mg b.d.

- Acupuncture

- Patient education and psychological support

- Application of 5% lignocaine patches

- Mirror therapy

- A 30-year-old woman with chronic lower back pain is assessed in an outpatient clinic. She tells you that her pain has improved with exercise and local heat application, but when she thinks about the pain it seems to get worse.Regarding this gate theory of pain, which of the following is most accurate?

- It applies mostly to nociceptive pain

- It is the basis of how transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) machines work

- A supraspinal input is required

- Inhibition occurs via Aδ fibres

- This theory does not apply to children

- A 73-year-old woman with metastatic breast cancer presents with a 4-month history of severe pain in her back, upper arms and legs. She has been on increasing doses of modified release oral morphine and paracetamol, and while this combination provides her some relief, she is troubled by drowsiness, pruritus, and constipation. At times she feels this is more distressing than her initial pain. Additionally, she is on warfarin for atrial fibrillation.

- A 35-year-old man has been admitted to the intensive care unit with a 55% total body surface area (BSA) burn. He is intubated and has been resuscitated as per the Parkland formula.Which of the following statements is correct?

- Should temperature spike above 38°C, take blood cultures and start broad spectrum antibiotics

- Enteral nutrition should be started as soon as possible

- Steroids are indicated as there is greater than 40% BSA burns

- Fluid resuscitation should be continued according to the Parkland formula even if polyuria develops

- If fluid management is optimal generalised oedema is unlikely to develop

- A hypertensive 68-year-old man on amlodipine is undergoing an elective abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. At the end of the operation the surgeon is prepared to release the infrarenal aortic cross-clamp.Which of the following interventions would mitigate the ensuing hypotension?

- Starting an infusion of noradrenaline at 0.5 µg/kg/min after cross-clamp release

- Starting an infusion of dobutamine at 5 µg/kg/min after the cross-clamp release

- Rapid infusion of 500 mL of colloid during cross-clamp release

- Tilting the table in reverse Trendelenburg position

- Optimising the intravascular volume during aortic cross-clamping

- A 74-year-old man is brought to the emergency department with palpitations. He has a heart rate of 156 beats per minute and atrial fibrillation on his ECG.Which one of the following would not warrant immediate direct current cardioversion?

- Blood pressure of 84/30 mmHg

- GCS of 12/15

- Bi-basal creptitations and tachypnea

- Sweating with cold clammy hands

- T wave inversion in lead aVR

- A 3-year-old boy suffers from dry and scaly skin, oral thrush, dandruff and dry hair, as well as poor vision in the dark. On examination he has xerosis and Bitot’s spots.

1. C The patient recalling that he has a foreign body in his eye

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans are often utilised for investigating the central nervous system as they provide images that show improved distinction between tissue types compared with computed tomography (CT) scans.

MRI scanning takes advantage of the fact that atomic nuclei within tissues naturally spin, generating their own small magnetic field. By applying a larger external field to a tissue, these spinning nuclei align with the field which has been applied. A second external field is then pulsed in a perpendicular fashion causing some nuclei to be pulled to an angle. This incorporates nuclear energy absorption, and they begin to wobble or precess – a term used to describe rotation around an axis different to that of original spin. Precession results in tissues producing rotational magnetic fields, the amplitude and specific frequency of which can be detected and used to form an image. As the nuclei return to their previous positions between pulses, they emit the energy they previously absorbed at the same frequency. The rate of their return depends on the elemental content of the nucleus (e.g. hydrogen or phosphorous) in addition to the molecule of which it is a part (e.g. water or fat). Different tissue types therefore return at different rates. By using a combination of magnetic field gradients and pulse configurations, detailed cross-sectional views can be obtained.

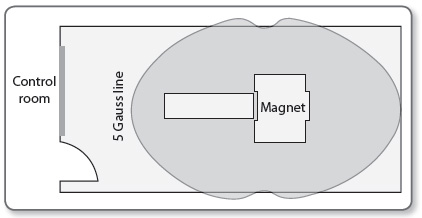

MRI scanners raise a number of safety concerns with regards to equipment. As the magnetic field is constantly present, anything containing ferromagnetic material will be attracted to it, turning them into projectiles. The field strength is measured in Tesla (T) and Gauss (G). 1T=10,000G. MRI scanners for medical imaging are usually 1.5T but sometimes 3T. The strength declines with distance from the magnet and contours are marked in Gauss lines on the floor of the MRI suite (Figure 1.2).

Beyond the 5G line no ferromagnetic material should ever be taken. This includes many items of equipment and implanted devices. Another concern with regards to equipment is the effect of radiofrequency energy resonating with material causing the dispersion of energy as heat. Patients can therefore suffer burns from any conductive material with which they are in contact.

13As a result of the above, all equipment is classified according to the hazard it poses under certain conditions such as magnetic field strength or in view of radiofrequency absorption. MR safe equipment can be used in all MR settings, MR conditional in specified environments, and MR unsafe in none of the aforementioned situations.

Monitoring in the MRI suite is essential and has evolved accordingly. MR compatible monitoring is standard, with many units using telemetric equipment to avoid any induced currents in long cables. MR compatible anaesthetic machines and infusion pumps are available; however standard equipment can be used with extensions to beyond the 5G line. The anaesthetic machine must be securely fixed to the wall and the pumps attached to their extensions through a port into the control room.

Pacemakers and implanted cardiac defibrillators are at risk of malfunctioning or displacing and so were, until recently, a strict contraindication to having an MRI. Technology has, however, advanced and there are now some MR-compatible models. There are also MR strategies and guidelines that have been described to limit risk in the event that an MRI is absolutely necessary for a patient with a standard device.

Cervical fixators, such as the halo device, vary in their classification. Some are MR safe and this, or the hazard of any other item, can be easily checked by referring to a list on www.MRIsafety.com.

Foreign bodies in the eye have the potential to migrate and cause bleeding into the vitreous, therefore contraindicating an MRI scan.

- Reddy U, White MJ, Wilson SR. Anaesthesia for magnetic resonance imaging. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain 2012; 12(3):140–44.

- Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Safety in magnetic resonance units: an update. Anaesthesia 2010; 65:766–70.

2. C Synchronised DC cardioversion with 100J

The ECG shows atrial flutter. Up to 40% of coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) patients will develop postoperative atrial fibrillation or flutter. The majority of these dysrhythmias occur within 48-hours and may be recurrent. Presence of atrial fibrillation or flutter is associated with an increase in hospital mortality as well as other complications including stroke.

Risk factors for the development of atrial fibrillation or flutter include:

- Atrial injury during cannulation

- Ischaemia

- Prolonged cardiopulmonary bypass time

- Use of post operative catecholamines

- Hypokalaemia and hypomagnesaemia

Although accompanied with reasonable haemodynamics, there is a clear fall in cardiac index (and hence output) as measured by the PiCCO. Atrial flutter may change to atrial fibrillation and rate control is rarely an option. Restoration of sinus rhythm should be the aim in this circumstance and this is best achieved with synchronised DC cardioversion.

14Although amiodarone is frequently used for atrial flutter, data concerning its use in this setting is surprisingly lacking. When using amiodarone, cardioversion may take hours rather than minutes. Another reason to avoid amiodarone in this circumstance would be the history of interstitial lung disease, which is a risk factor for exacerbation of any lung fibrosis that may be caused by amiodarone.

Rate controlling agents such as metoprolol and digoxin would not be optimal treatment here.

Atrial pacing is a viable option but would usually be performed at a rate 10–15 bpm higher than the atrial flutter rate. If the ventricular rate rises to match the atrial rate, the pacemaker frequency can then be reduced (i.e. the rhythm is entrained) to an acceptable rate. This may lead to conversion to sinus rhythm (or atrial fibrillation!). Given this patient is already sedated and ventilated, it is quicker and more effective to perform DC cardioversion.

As well as addressing strategies for cardioversion, it is also imperative that other contributing factors for the development of any dysrhythmias are addressed:

- Hypoxaemia

- Hypercarbia

- Electrolyte disturbances

- Other causes of myocardial ischaemia e.g. graft failure

- European Society of Cardiology. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2010; 31:2369–429.

3. B Vancomycin 1.5 g, gentamicin 400 mg

Common pathogens in cardiac surgery are Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. In addition, this man has evidence of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) colonisation, so any prophylactic antibiotics must cover this organism (vancomycin or linezolid). Most centres also administer some gram negative cover such as an aminoglycoside (gentamicin at 5 mg/kg) or a fluoroquinolone (ciprofloxacin).

Although the skin reaction reported after penicillin may not be significant, it is prudent to avoid penicillins thus flucloxacillin and co-amoxiclav should be avoided. Vancomycin 1.5 g with gentamicin 400 mg provides gram-positive (including MRSA) and gram-negative cover and is the correct regimen for this patient. The dose of vancomycin is 15 mg/kg and should be given as an infusion. The combination of cefuroxime and metronidazole does not have MRSA cover and although clindamycin with ciprofloxacin gives good gram positive, gram negative and MRSA cover, the use of untargeted ciprofloxacin is often discouraged due to the speed by which plasmid mediated resistance can occur.

Other elements of perioperative care that may reduce the incidence of surgical site infection include patient warming, tight glycaemic control, hair removal and the sterility of instruments and the surgical field.

- Bratzler DW, Dellinger EP, Olsen KM, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery. Surg Infect 2013; 14(1):73.

Tracheostomy airway emergencies can lead to significant morbidity and mortality if not managed correctly. Laryngectomy patients do not have an upper airway so crucially cannot be intubated or oxygenated orally. They are unlikely to obstruct when lying flat so sitting them more upright is not the immediate airway priority. In this scenario following a call for help and application of oxygen, the tracheostomy tube patency needs to be assessed as a priority.

With double lumen tracheostomy tubes, the initial step is to remove the inner tube which will clear any secretions if these are causing a blockage. Following inner tube removal, passage of a suction catheter should be attempted to confirm airway patency and also help clear any further secretions within the tracheostomy tube. If the suction catheter fails to pass, deflation of the tracheostomy tube cuff may improve airflow if the tracheostomy tube is partially displaced. If the clinical condition fails to improve following cuff deflation, the tracheostomy tube may be completely blocked or displaced, preventing the patient to breathe around the tube adequately and should therefore be removed. Attempting hand ventilation through a tracheostomy tube to confirm airway patency is hazardous, since significant surgical emphysema can ensue in the presence of tube displacement making subsequent airway management more difficult. Figure 1.3 provides a graphical suggestion for the steps to be taken in the assessment of tracheostomy tube patency in post-laryngectomy patients.

16Therefore, this patient requires removal of the inner cannula for further assessment and management of the cause of her respiratory distress.

- McGrath BA, Bates L, Atkinson D, Moore JA. Multidisciplinary guidelines for the management of tracheostomy and laryngectomy airway emergencies. Anaesthesia 2012; 67(9):1025–41.

- Regan K, Hunt K. Tracheostomy management. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain 2008; 8(1):31–35.

5. E Extended course of low molecular weight heparin post discharge

The risk of venous thromboembolic disease (VTE) after a day surgery procedure is lower than after in-patient procedures as surgery is generally less invasive and mobilisation is earlier. However, more complex and longer procedures in higher risk patients are increasingly being performed in this setting. The 2010 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for the prevention of VTE includes day surgery as a specific cohort of patients and recommends that mechanical prophylaxis should be used if one or more risk factors are present. Pharmacological prophylaxis should be added depending on ‘patient factors and clinical judgement’.

- Surgical procedure with a total anaesthetic and surgical time of more than 90 minutes, or 60 minutes if the surgery involves the pelvis or lower limb

- Acute surgical admission with inflammatory or intra-abdominal condition

- Expected significant reduction in mobility

- One or more of the risk factors below:

- Active cancer or cancer treatment

- Age over 60 years

- Critical care admission

- Dehydration

- Known thrombophilia

- Obesity (body mass index [BMI] over 30 kg/m2)

- One or more significant medical comorbidities (for example: heart disease, metabolic, endocrine or respiratory pathologies, acute infectious diseases, inflammatory conditions)

- Personal history or first-degree relative with a history of VTE

- Use of hormone replacement therapy

- Use of oestrogen-containing contraceptive therapy

- Varicose veins with phlebitis

Pharmacological prophylaxis should be continued for 5–7 days if significantly reduced mobility is expected. This patient has three risk factors and extended pharmacological prophylaxis is indicated. In addition she will have a lower limb plaster cast, where NICE recommends that prophylaxis should be continued until the cast is removed after discussion with the patient and evaluation of risks and benefits. The exact duration will vary between centres.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Venous thromboembolism – reducing the risk. CG no 92. London: NICE, 2010.

- British Association of Day Surgery (BADS). Organisational issues in pre operative assessment for day surgery. London: BADS, 2010.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), is of major clinical significance given that up to a quarter of inpatients with risk factors may be affected, albeit subclinically. Candidates will be familiar with the risk factors for VTE (see above) but also should be comfortable with the drug treatment strategies available and their complications.

Mechanical methods

Anti-embolism stockings or thromboembolic deterrent stockings (TEDS), are graded to provide increased compression from distal to proximal. They are effective at promoting venous return and increasing the speed of blood flow, but not suitable for all patients, such as those with arteriopathy. Intermittent calf and thigh compression devices produce pressures of approximately 40 mmHg 10 times per minute to emulate the limb muscle pump.

Heparins

Unfractionated heparin is a naturally occurring antithrombin binder. This inhibits factor Xa and thrombin and in higher doses also has an antiplatelet function. Low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) is more effective than subcutaneous heparin, has a lower risk of bleeding, and less anti-platelet effects. It is more convenient with once daily administration, but is less controllable than a heparin infusion, and accumulates in renal failure. It will not usually affect the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), which is a useful monitor of unfractionated heparinisation.

Warfarin

Warfarin has the advantage of being given orally, and has similar risks of bleeding as LMWH. It can be monitored using the international normalised ratio (INR).

Fondaparinux

Fondaparinux is a synthetic saccharide which emulates the structure of the heparin anti-thrombin binding site. It indirectly inhibits factor Xa, and is given by subcutaneous daily injection. It is more effective at preventing VTE than LMWH, but also at producing bleeding. The half-life is long, and the drug-free time before neuraxial block is thus 36 hours. It has a lower incidence of HIT, and has been used as a LMWH substitute in this condition.

Others

Lepirudin is a hirudin derivative made as a recombinant protein in yeast, whose main use is in heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). It directly inhibits thrombin and due to its short half-life is administered by a continuous infusion and is monitored with the aPTT. Due to manufacturer cessation of production in April 2012, lepirudin is no longer available in the UK. Notably, this withdrawal was not due to any safety concerns.

Danaparoid is a heparinoid that inhibits factor Xa, and can be used in patients with HIT. There is a need for close monitoring as some HIT cross reactivity does occur. It has now replaced the use of lepirudin in the management of HIT in the UK due to the aforementioned withdrawal.

18Dabigatran is an orally administered direct thrombin inhibitor licensed for VTE prophylaxis after surgery. It does not require monitoring but also lacks any method to reverse the anticoagulant effect.

Rivaroxaban is a direct oral inhibitor of factor Xa that is becoming more common. Previously only for postoperative VTE prophylaxis, it is now being used in atrial fibrillation and in Europe as an adjunct to aspirin and clopidogrel in acute coronary syndromes.

The likely diagnosis in the above patient is an episode of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). HIT is an immune-mediated IgG response to an immunogenic component of heparin, leading to thrombocytopenia. This occurs in around 3% of patients as a consequence of treatment with unfractionated heparin, and less-so at a rate of 0.1–1% with LMWH preparations. Paradoxically, the risk of thrombosis is increased to 50% at this time, so alternate forms of anticoagulation are needed. Platelet counts should be monitored from day 4 – 14, which is the risk period for antibody formation.

Although the diagnosis is not absolutely confirmed, the question forces you to respond and treat in the safest way possible. If HIT is a possibility then a heparin infusion should be avoided, as should LMWH, as this can also precipitate the condition. In addition, the dose of LMWH is probably too high, given that she is no longer on anticoagulant treatment. Aspirin may or may not be indicated for this patient in terms of primary cardiovascular prophylaxis, but does not have any role in thromboprophylaxis. Of the two HIT-safe options, fondaparinux and danaparoid, only danaparoid has no association with HIT. Fondaparinux has a very low rate of giving rise to HIT and is sometimes used off-license as a treatment. However, in this scenario the long half-life makes fondaparinux irreversible and uncontrollable in the immediate postoperative phase. From day 2 onwards, without bleeding, fondaparinux would represent a good choice for prophylaxis with adequate monitoring of platelets.

- Barker RC, Marval P. Venous thromboembolism: risks and prevention. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain 2011; 11(1):18–23.

7. D Trigeminocardiac reflex

The horizontal Le Fort I osteotomy is a common procedure used to correct maxillary deformities and knowledge of the surgical technique and relevant anatomy is useful in recognising and treating complications. Surgery involves an intraoral incision and the formation of a transverse maxillary osteotomy that extends to the pterygomaxillary junction. The maxilla is then separated from the upper face along this osteotomy plane by a down-fracture and fully mobilised to aid surgery.

Bleeding is a recognised complication during the down-fracture since the bony mid-face receives a rich blood supply and is in close proximity to an extensive venous plexus. The blood vessels most likely to be injured during the down-fracture are the pterygoid vessels, palatine and alveolar arteries, or on rare occasions the internal carotid. In order to visualise the source of bleeding and achieve haemostasis, completion of the down-fracture is often required. It is unusual for an acute haemorrhage to present with a severe bradycardia as described in the above case.

19Venous air emboli can occur during any head and neck surgery where open veins are exposed to the atmosphere. However, end-tidal carbon dioxide levels would be expected to fall as a result of an increase in physiological dead space and intrapulmonary shunting which is not observed in the above case.

A nasal endotracheal tube is usually the airway of choice when correcting for maxillary retrusion, since the jaw is frequently closed and wired to ensure normal alignment of the upper and lower teeth. During the osteotomy and down fracture, the nasal tube may be damaged resulting in impaired gas exchange and secondary haemodynamic compromise. In such a situation, the airway (which is now likely to be difficult) needs to be re-established. This scenario is unlikely in the above case since the oxygen saturations, end tidal carbon dioxide levels and airway pressures remain unchanged.

The Le Fort I osteotomy can also cause nerve damage and pressure effects to cranial nerves II-VII due to their proximity to the surgical field. A recognised complication of the maxillary down-fracture in particular is the generation of the trigeminocardiac reflex. This reflex occurs as a result of pressure on the cranial nerve V (trigeminal nerve) initiating a vagal reflex causing a severe bradycardia which may even progress to asystole. Cessation of the down-fracture and return of the jaw to its original position can increase the heart rate, as can administration of anticholinergic drugs. The isolated bradycardia and hypotension in relation to the down-fracture in the above scenario makes this reflex the most likely cause.

Remifentanil use in maxillofacial surgery is increasing in popularity due to its favourable pharmacokinetic profile and its useful contribution to deliberate hypotension. Severe bradycardia and hypotension are recognised complications of remifentanil use, however the temporal relationship between the down-fracture and the bradycardia in the above case make the trigeminal reflex more likely.

- Beck J, Johnston K. Anaesthesia for cosmetic and functional maxillofacial surgery. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain 2013 doi:10.1093/bjaceaccp/mkt027.

- Miloro M, Kolokythas A. Management of complications in oral and maxillofacial surgery. 1st Ed. New York:John Wiley & Sons Inc, 2012.

8. C Use intravenous esmolol during procedure

During electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) an electrical current is applied to the brain via transcutaneous electrodes to induce a generalised therapeutic seizure lasting between 10–120 seconds. There is a biphasic physiological response. The seizure causes an immediate direct stimulation of the vagal parasympathetic outflow, which can lead to transient bradycardia and hypotension, and rarely asystole.

Premedication with an anticholinergic agent is often used to attenuate this effect. This is followed by a more prominent catecholamine mediated sympathetic response, which peaks 3–5 minutes after therapy, causing a tachycardia, and hypertension and may give rise to tachyarrhythmias.

This sympathetic response can be attenuated using a variety of agents. Beta blockers have been shown to be the most effective in controlling both heart rate and mean arterial pressure. Due to the risk of initial bradycardia short acting agents such as 20esmolol or labetalol given just prior or during the procedure may avoid accentuating the parasympathetic response compared to longer acting agents. Esmolol is preferred as it reduces the peak systolic blood pressure more than labetalol while labetalol may be associated with a shorter seizure duration.

Calcium channel blockers can also be effective to control arterial pressures but reflex tachycardia may occur with nifedipine. Remifentanil has been shown to reduce both the heart rate and blood pressure and does not have an effect on seizure duration, though use of an infusion may not be available or suitable for these short procedures.

- Uppal V, Dourish J, Macfarlane A. Anaesthesia for electroconvulsive therapy. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain 2010; 10(6):192–197.

9. C Arrange an urgent MRI scan and inform the neurosurgeon

There are many benefits for neuroaxial drug delivery. However, we need to balance the advantages against the risk of complications such as infection, nerve damage and haematoma.

In the third National Audit Project (NAP 3) report, the incidence of epidural abscess after central neuraxial block (CNB) was quoted as 2.1 in 100,000. Although this is considerably lower than previous studies, epidural abscess is still a very serious complication of CNB and can lead to permanent neurological damage. In the above scenario, the patient has signs and symptoms of an established epidural abscess that needs decompression immediately.

We should recognise patients at increase risk of spinal infection before commencing the CNB, with risk factors including:

- Immune compromised patients

- Patient with local or systemic infection

- Long-term vascular access

- Long duration of epidural catheterisation

- Difficult CNB or a bloody tap after epidural

- Prolonged hospital stay

- Disruption of the spinal column, e.g. surgery or trauma

Following epidural catheter insertion, catheter site checks and regular temperature monitoring are very important to recognise epidural abscess.

The classical presentation of epidural abscess is of pyrexia, back pain and progressive abnormal neurology of the lower half of the body. However, 1 in 4 patients have no back pain. Therefore, a high index of suspicion is required to diagnose epidural abscess.

Advice from neurosurgeons, neurologists, radiologists and microbiologists are needed early in established epidural abscess.

The most important action when we suspect epidural abscess is to organise MRI with gadolinium. This will help to decide whether open or percutaneous drainage should be used.

21In this example, arranging an MRI scan and informing the neurosurgeons are the first and most important steps to perform because early diagnosis and surgical decompression is needed. Although option E is correct, it is time consuming and delays the diagnosis. Once muscle weakness is present, only 20% patients regain full function, even after surgery.

A full infection screen including blood cultures is mandatory if an epidural abscess is suspected. At the same time, it is essential to remove the epidural catheter, as well as stop the epidural infusion, and send the catheter tip for culture and sensitivity. As solely stopping the infusion is inadequate, options A, B and D are insufficient management options.

The most common microorganism found in spinal infection is Staphylococcus. Initial antibiotic therapy should be empirical and then modified depending on the culture and sensitivity results, while treatment must be guided by microbiological input.

Intravenous antibiotics are required initially for 2–4 weeks, followed by a prolonged course of oral antibiotics. Regularly checking of inflammatory markers, back pain and neurology should be used to monitor the response to antibiotics.

- Royal College of Anaesthetists. Major complications of central neuraxial blocks in the United Kingdom: the 3rd National Audit Project (NAP3) of the Royal College of Anaesthetists, 2009. Br J Anaesth 2009; 102(2):179–90.

- Simpson KH, Al-Makadma YS. Epidural drug delivery and spinal Infection. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain 2007; 7(4):112–15.

- Gosavi C, Bland D, Poddar R, Horst C. Epidural abscess complicating insertion of epidural catheters. Br J Anaesth 2004; 92:294–95.

10. D 100 mm length, short bevel peripheral nerve block needle

When performing nerve blocks, the length of the block needle is an essential consideration. Longer needles might have potential tissue damage if advanced further than needed, while the shorter needle may not be long enough to reach the nerve.

The ideal needle length for peripheral nerve blocks is:

- 25 mm – Interscalene

- 50 mm – Cervical plexus, supraclavicular, axillary, femoral and popliteal ('posterior approach')

- 100 mm – Infraclavicular, paravertebral, lumbar plexus, sciatic (‘posterior approach’) and popliteal (‘lateral approach’)

- 150 mm – Sciatic (‘anterior approach’)

There are two types of nerve block needles: cutting tip needle and pencil point tip needle (see Figure 1.4).

Cutting tip needles might be long bevel (15°) or short bevel (30–45°). Long bevel needles are more likely to cause nerve damage by causing sharp nerve penetration. Although the nerve damage caused by a short bevel needle is less frequent, the damage will be more severe.

Pencil point needles are believed to penetrate tissue rather than cut through it, thus providing an improved feel of anatomical layers through which they pass. It is not clear whether a pencil point needle or a short bevel needle is safer to use.

The most frequently used needle in the current practice is the short bevel one. It offers more resistance as it passes through the tissue planes, provides better tactile feedback than long bevel needles and is less likely to cause nerve damage. Thus in this clinical scenario, the most appropriate needle for a lateral approach popliteal nerve block is a 100 mm, short bevel needle.

- Jeng CL, Torrillo TM, Rosenblatt MA. Complications of peripheral nerve block. Br J Anaesth 2010; 105(suppl 1):i97–i107.

- Hadzic A. Textbook in Regional Anaesthesia and Acute Pain Management. 1st ed. Columbus, OH: McGraw-Hill Medical, 2006.

11 D Perform a modified RSI with 1.5 mg/kg suxamethonium, after 2 µg/kg fentanyl and propofol and manual in-line stabilisation of the cervical spine

This question relates to the management of the patient with traumatic brain injury (TBI). TBI is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in young patients, with over 10% of injuries falling in the moderate to severe category. The principles of management are those relevant to all neurosurgical emergencies and neurotrauma patients.

Initial assessment and resuscitation

Should be along the familiar treatment algorithm of ABCDE, but with treatment and stabilisation of each problem simultaneously as the assessment continues.

Even one episode of hypotension has been shown to double mortality. The aim is to maintain cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP), in the face of raised intracranial pressure (ICP) as CPP = MAP – ICP. International targets differ slightly, but a widespread MAP target is 90 mmHg. Fluid resuscitation to normovalaemia would be the logical first step, with vasopressors following if required. Crystalloid is best, with some evidence of harm with albumin colloid. Hypotonic dextrose solutions must be avoided (unless hypoglycaemic), as they contribute to tissue oedema.

Airway/ventilation

Intubation is indicated for a deterioration in Glasgow coma scale (GCS), or a GCS of < 8, or if there is a failure of the patient's protective reflexes. Any disturbance in oxygenation or ventilation leading to hypoxia or hypercapnia is likewise a mandatory indication as hypoxic episodes are shown to worsen prognosis. Hypercapnia will increase cerebral blood flow (CBF) and thus ICP, so must be controlled; similarly a patient hyperventilating to hypocapnia must move to controlled ventilation as they will compromise their cerebral perfusion. Other indications include those that may compromise the airway if not dealt with, such as bilateral mandibular fractures, oral bleeding, or seizures. Targets again differ, but a PaO2 of > 10 kPa and a PaCO2 in the normal range of 4.5–5 kPa are assumed to be safe.

Managing ICP

Outside of a neurosurgical centre, intracranial hypertension is either a presumptive diagnosis, or made when so severe as to bring about herniation and associated pupillary unresponsiveness. Where facilities exist for monitoring, the level at which treatment should begin, is > 20–25 mmHg.

Hyperosomolar fluids such as mannitol and 3% saline draw fluid from the intracellular space back into the interstitium and vasculature. Fewer complications are seen with hypertonic saline and doses depend on the concentrations available, but 3 ml/kg of 3% or 2 mL/kg of 5% are reasonable, titrated to a serum sodium of < 155 mmol/L.

Hyperventilation has been shown to compromise cerebral perfusion, and is thus reserved for severe cases resistant to other treatments. A temporary course of hyperventilation titrated to a Paco2 of 4–4.5 kPa may be used.

Hypothermia reduces ICP and cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2), and is used in neurosurgical centres for this reason. The target temperature, and duration to achieve benefit are not known, as no benefit has yet been reliably shown. Most would ensure mild hypothermia (35°C), and ensure prevention of fevers, which are known to be harmful.

Adequate sedation (reducing CMRO2) and muscle relaxation preventing coughing and associated rises in ICP is essential. This is extrapolated using barbiturates for burst suppression in some cases of raised ICP, but is associated with significant hypotension.

In the above patient, the GCS is E1 V2 M3 = 6/15, and, in the context of a head injury this represents an indication for intubation. The patient meets the criteria for 24immediate CT scanning, and the need for imaging in this patient also mandates securing of the airway prior to the scan.

This is a dangerous mechanism of injury, and the C-spine is compromised until proven otherwise. Therefore C-spine control is needed for intubation and scanning. Clearing this clinically is no longer possible due to the conscious level. Even if the GCS were 15, with a distracting fractured arm, one cannot clear the neck confidently without imaging.

The final discriminator here is choice of drugs used. The priority is rapid control of the airway with muscle relaxation, whilst preventing either hypertension, (and raised CBF and therefore increased ICP), or hypotension (with a fall in cerebral perfusion pressure). Most would achieve the former by adjunctive use of an opioid, and the latter with cautious use of induction agent. Ketamine has recently been shown to have no effect on increasing ICP, contrary to traditional teaching, but the dosing of 3 mg/kg is high, and a dosing of 1.5–2 mg/kg is likely sufficient. Similarly, for muscle relaxation, classical teaching has urged against suxamethonium because of a transient rise in ICP. However, the rise is small and for the most part offset by the fall in perfusion pressure caused by co-administration of induction agents. Therefore the most appropriate course of action in this patient would be to perform an RSI with fentanyl, suxamethonium and propofol and manual in-line cervical stabilisation.

- Dinsmore J. Traumatic brain injury: an evidence based review of management. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain 2013; 13(6):189–95.

12. D Insertion of invasive arterial and central venous catheter

This patient requires transfer for specialist surgical services. Although not in extremis his condition may become compromised during transfer and adequate resuscitation and pre-transfer planning are essential.

Motion artefact may make non-invasive blood pressure (NIBP) readings unreliable and continuous invasive arterial blood pressure (ABP) monitoring in these situations is more appropriate. Central venous catheters provide a reliable form of intravenous access and allows for the use of inotropic or vasopressor support should the need arise during transfer.

The use of a pulmonary artery catheter and cardiac output measurements by thermodilution is not practical during transfer and will not contribute to this patient’s management.

Intubation and ventilation monitored with continuous capnography should occur pre-transfer in patients in whom the airway or ventilation may be compromised, neither of which are a concern in this case. Pericardial clots may prevent adequate pericardial drainage and blood may further accumulate. Pericardiocentesis in a non-cardiac centre without immediate surgical support should be carefully considered, and may unnecessarily delay transfer. It is indicated in patients with significant haemodynamic compromise, although a haemodynamically unstable patient with a penetrating chest wound likely warrant a thoracotomy. Aggressive fluid resuscitation in patients with penetrating injuries should be cautious and goals should be to 25maintain an adequate filling pressure, heart rate and contractility. Blood should be cross-matched and available to administer in the ambulance if required, and tranexamic acid would be an appropriate adjunct in this circumstance.

- Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Interhospital transfer. AAGBI Safety Guideline. London: AAGBI, 2009.

- Intensive Care Society (ICS). Guidelines for the transport of the critically ill adult. London: ICS, 2002.

13. C Perform a recruitment manoeuvre and incrementally increase the PEEP to above 14 cmH2O

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) was first described in 1967 by Ashbaugh et al to describe tachypnoea, pulmonary infiltrates, decreased pulmonary compliance, atelectatic lungs with alveolar oedema and hyaline membranes on pathological examination.

The first formalised diagnostic criteria were created by the American-European Consensus Conference (AECC) in 1994 and have since evolved. This included:

- An acute clinical course

- Bilateral infiltrates on the chest radiograph

- No atrial enlargement or left ventricular failure

- A severity classification dependent on the PaO2/FIO2 ratio (PFR)

- ARDS was classified as a PFR < 200 mmHg

- Acute lung injury (ALI) was classified as a PFR of > 200 < 300 mmHg

In 2012 the Berlin definition by the AECC superseded the original classification:

Respiratory failure now needs to occur within a week of a known initiating process. Heart failure no longer needs to be excluded but must not fully explain the patients respiratory failure. Acute lung injury no longer exists, and grades of severity of ARDS has replaced the older classification (Table 1.2). The new definition offers better predictive information for duration of treatment and the mortality.

This patient has severe ARDS as defined by his PFR and is at risk of dying from hypoxia. There is an escalation protocol on how to manage such a patient, starting with simple manoeuvres and ending with desperate measures:

- Recruitment manoeuvres to improve oxygenation. There are several methods, which are detailed by Lapinsk and Mehta. Most involve a transient increase in PEEP and peak ventilator pressures, which can be performed using a manual technique or the ventilator.

- Other ventilator settings such as reverse inspiratory: expiratory (I:E) time ratios may be beneficial.

- Fluid balance management is key for more long-term management. Recent evidence suggests that avoiding a positive fluid balance increases ventilator-free days and may reduce mortality.

- Prone positioning has recently been shown to improve oxygenation, improve 28-day and 90-day mortality and is not associated with an increase in complications if performed properly. It should be commenced early in the disease process and for a minimum of 17–24 hours per day.

- Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is becoming increasingly used for refractory respiratory failure in a select cohort of patients with reversible conditions, however caries a significant risk of haemorrhage. It can only be carried out in regional centres.

Two therapies investigated previously include steroid administration and oscillation ventilation. Both these interventions do not improve outcome, and in the case of oscillation may infer risk if used by a centre without significant experience. Therefore they are no longer recommended treatment options for ARDS.

In summary, at present the only interventions for ARDS that infer a mortality benefit is ARDSNet ventilator strategy, fluid balance managing and most recently prone ventilation. In the above scenario the patient was not on an optimum ventilator setting. Recruitment manoeuvres would be the most important first intervention followed by maintenance of recruitment with appropriate ventilator settings.

- Mackay A. Acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain 2009; 9(5):152–56.

- Lapinsk S, Mehta S. Bench-to-bedside review: recruitment and recruiting maneuvers. Crit Care 2005; 9(1):60–65.

14. B Intravenous crystalloid bolus of 20 mL/kg followed by a noradrenaline infusion to maintain blood pressure

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) are a class of drug used to treat depression, chronic pain syndromes and attention deficit disorder in children. Amitriptyline is the most commonly used in clinical practice. Overdose occurs at all ages including accidental overdose. TCAs are some of the most frequently overdosed medications and contribute to up to 300 deaths per annum in the UK.

Cardiovascular collapse is due to a sodium channel ‘stabilising effect’ due to blockade of fast sodium channels in the myocardial conduction system. This leads to an increase in QRS duration initially and may progress to decreased myocardial excitability, bradycardia and asytole. In addition a dose-dependent decrease in myocardial contractility occurs due to noradrenaline (NA) and serotonin re-uptake inhibition. Alpha-1 adrenergic receptor blockade causes profound vasodilatation, which leads to distributive shock.

27Altered mental state resulting in confusion or agitation may be as a result of central anti-histaminic and anti-cholinergic activity. Increasing central nervous system levels of noradrenaline and serotonin reduces the seizure threshold.

The management of the patient described above should include an ABC approach to protect the airway. All options are viable:

- Once the airway is protected, if ingestion is within an hour of presentation activated charcoal may be considered but this will only prevent further gastrointestinal absorption and not impact the current emergent problem of hypotension and may in fact worsen it.

- Fluid and vasopressors are the most important initial management. This will counteract the distributive shock component as described above. This may be sufficient to improve mean arterial pressure resulting in a decrease in heart rate.

- The high sodium load found in sodium bicarbonate stabilises the myocardium and may prevent arrhythmias. It is indicated if the QRS width is over 100 msecs. An alternative treatment is hypertonic saline if no metabolic acidosis is present. Increasing plasma pH also has the effect of increasing drug protein binding, which can be achieved by hyperventilation.

- Amiodarone and other class 1a and 1c anti-arrhythmic agents should be avoided as they increase the cardiac action potential. Both lignocaine and magnesium have been used for arrhythmia management in TCA overdose.

- There are case reports that lipid emulsion has been used successfully in cardiac arrest secondary to TCA overdose by sequestering plasma drug and reducing the active concentration. If used, this should follow the same protocol as for local anaesthetic toxicity.

A multi-faceted approach is required however the initial management should focus on airway control, volume expansion and management of vasoplegia before moving onto more complex treatment options.

- Body R, Bartram T, Azam F, Mackway-Jones K. Guideline for the management of tricyclic antidepressant overdose. Emerg Med J 2011; 28(4):347–68.

- Ward C. Oral poisoning: an update. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain 2010; 10(1):6–11.

15. D Vital capacity < 15 mL/kg

The symptoms of progressive and ascending motor weakness with the antecedent history of a viral infection suggest Guillain–Barré syndrome. Guillain–Barré is a collection of diseases that result from acute inflammatory demyelination leading to the hallmark signs of ascending muscle weakness and areflexia. Sensory and autonomic function can also be affected by Guillain–Barré.

The pathophysiology of Guillain–Barré appears to be an immune mediated reaction to a prior infection, commonly upper respiratory tract infections or Campylobacter jejuni. Autoantibodies (such as antiganglioside autoantibodies) initiate either a cascade of myelin destruction or axonal damage; the latter results from C. jejuni infection with a worse prognosis.

Early detection of the need for intubation is imperative as rapid deterioration can ensue. Indications for intubation predominantly include respiratory failure 28secondary to muscle weakness or the presence of bulbar symptoms necessitating airway protection.

Whilst clinical signs of respiratory failure such as tachypnoea, hypoxia and hypercapnia will strongly suggest the requirement for intubation, these are relatively late signs. Serial vital capacity (VC) measurements should be taken and management in a critical care area should be considered when VC < 20 mL/kg. Intubation should be carefully considered when measurements fall below 15 mL/kg in the presence of bulbar symptoms or rapidly progressive disease. Rapid sequence induction is recommended due to the raised aspiration risk. In addition to full AAGBI monitoring, invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring should be instituted, particularly in the presence of autonomic instability. Due to reports of an exaggerated hyperkalaemic response, depolarising muscle relaxants should be avoided.

Critical care management should include consideration of immunotherapy in liaison with specialist teams. Intravenous immunoglobulin or plasma exchange is the mainstay of current management, while steroids do not appear to have a role.

- Richards KJC, Cohen AT. Guillain‐Barré syndrome. BJA CEPD Reviews.2003;3(2):46–49.

- Yuki N, Hartung HP. Guillain–Barré syndrome. N Engl J Med 2012; 366(24):2294–304.

16. B Injury

Acute kidney injury (AKI) describes an abrupt decline in renal function. A number of classification systems have been devised to further the definition and staging of AKI. Three in common use are the RIFLE criteria (2004), AKIN criteria (2009) and KDIGO (2012). All three rely on a defined creatinine rise with or without criteria for urine output. There is an increasing recognition that serum creatinine may not detect early AKI and the role of renal injury biomarkers, such as neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), is under investigation.

Of the three criteria to describe AKI, none have shown clinical superiority, although the AKIN criteria are more sensitive. The question uses the RIFLE criteria as this is commonly referred to in UK practice. According to RIFLE, AKI is subdivided into five progressive stages based on creatinine rise and urine output. Further information regarding the AKIN criteria can be found in question 10.13.

The patient described in the question has doubled his creatinine from baseline and his urine output has been less than 0.5 mL/kg/hr (35 mL/hour) for 12 hours. He therefore fulfills the RIFLE ‘injury’ criteria (Table 1.3).

| |||||||||||||||||||

29The morbidity and associated mortality from AKI is high both within and outside the critical care environment. Prevention, early recognition (using criteria) and good adherence to the principles of management should be a part of routine care. The principles of management include treating the underlying cause, optimising renal perfusion, withholding nephrotoxic agents and, where appropriate, renal replacement therapy.

The clinical importance of AKI has lead to a recent National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline and the London Acute Kidney Injury Network releasing an ‘AKI bundle.’

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Acute Kidney Injury (CG169). 2013. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Available from: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG169

- London Acute Kidney Injury Network. Acute Kidney Injury Bundle. 2013. Available from: http://www.londonaki.net/news/downloads/AKI_bundle-GSTH.pdf

17. B Methicillin sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA)

The case described has features consistent with the development of pneumonia during the provision of invasive mechanical ventilation (MV). Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) has traditionally been defined as tracheobronchitis or pneumonia occurring more than 48 hours after initiation of MV. This definition relies on a high index of suspicion with confirmation based on clinical, radiological and microbiological evidence. The definition of VAI remains a controversial area. A recent Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) guideline has suggested that VAP may not require a positive microbiological diagnosis.

Clinical scoring systems, such as the Clinical Pulmonary Infection Score (CPIS), can help to objectify the diagnosis of VAP. CPIS is based on temperature, white cell count, appearance of tracheal secretions, new infiltrates on chest radiology and oxygenation indices. A score of greater than 6 is suggestive of VAP. However the validity of this score has been questioned.

The most commonly associated causative organisms tend to relate to the timing of the infection from the onset of MV. In the case described here, the onset is early (< 5 days) and as such is most commonly associated with MSSA and Haemophilus influenzae. The commonest bacterial pathogens in late onset VAP (> 5 days) are aerobic gram negative bacilli (AGNB) such as Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, Enterobacter and Acinetobacter. Drug resistant microbes such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE) are also causative organisms for late onset VAP. The value of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) over and above blind endotracheal aspiration is keenly debated.

The management of VAP is supportive with continuous microbiological surveillance and antimicrobial therapy based on local policies in combination with microbiological advice. The prevention of VAP is the focus of a Department of Health (DoH) High Impact Intervention Care bundle. This document outlines six key areas of recommended good practice:

- Elevation of the head of the bed to 30–45° (though trials of supine and even head down positioning are currently in progress)

- Oral hygiene with chlorhexidine 6 hourly and tooth brushing 12 hourly

- Subglottic aspiration in patients expected to be intubated for > 72 hours (complex and controversial evidence for this intervention)

- Tracheal cuff pressure measured 4 hourly and maintained between 20–30 cmH2O

- Stress ulcer prophylaxis prescribed only in high risk patients according to local protocols and reviewed daily (though this contradicts the earlier DoH, ‘Ventilator care bundle’)

- Kalanuria AA, Zai W, Mirski M. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in the ICU. Crit Care. 2014;18(2):208.

- Department of Health. High impact intervention care bundle to reduce ventilation-association pneumonia. London: Department of Health, 2010.

18. E Site a spinal catheter, inform midwife and perform subsequent top-ups yourself

Accidental dural puncture (ADP) is a well-known complication of epidural anaesthesia, being said to occur in 0.2–4% of cases. Parturients are at risk due to difficulty in positioning and being ‘moving targets’. In this case, there is the added risk of multiple attempts at insertion and a high body mass index (BMI). This case is typical of a pressurised situation on labour ward and the clinical setting must be taken into account when deciding how to manage the ADP.

Repeating the attempt is a potential option but is not the best line of management due to the difficulty of finding the space with multiple attempts already having been undertaken.

The chance of a colleague being available to assist at this time is slim, as opposed to during a day shift. Although this is a possibility, a colleague may also find this epidural difficult to perform, and there may be a significant delay before they can attend to help.

Ultrasound can help to locate the depth, but even with optimum conditions, this will be difficult in a lady of this size, especially if you are unfamiliar with this technique. Finding the ultrasound machine and the correct probe may also prove challenging in the clinical circumstances.

A remifentanil PCA is a potential alternative, but in this situation, the lady has a high risk of needing further intervention due to the position of the baby. Therefore, a spinal catheter is the best option. To reduce the risks of neurological damage, no more than 3 cm is left inside the subarachnoid space. The catheter must be clearly labelled as intrathecal, and both the midwife and mother must be informed. Top-ups must be given only by the anaesthetist. A suggested regime may be 2.5 mL of low dose mixture (0.1% levobupivacaine + 2 μg/mL fentanyl) every 2–4 hours. This can also be used if the patient goes on to need any operative intervention. There is also some evidence that introducing a spinal catheter may reduce the incidence of post dural puncture headache.

- Sharpe P. Accidental dural puncture in obstetrics. BJA CEPD Reviews 2001; 1(3):81–84.

- Palmer CM. Continuous spinal anesthesia and analgesia in obstetrics. Anesth Analg 2010;111(6):1476-9.

3119. C Commence MgSO4 infusion at 1 g/hour, give a further 2 g MgSO4 bolus, secure airway with ETT and continue supportive management

Pre-eclampsia is one of the causes of maternal death and since it is well managed, it is not often that patients present with eclamptic seizures. The MAGPIE Trial demonstrated that MgSO4 significantly reduces the risk of eclampsia and this is standard management in these cases. The initial dose of MgSO4 is 4 g over 5–10 minutes followed by an infusion at 1 g/hour for 24 hours post-partum. Any subsequent seizures may be treated with a further bolus of 2 g MgSO4. Phenytoin and diazepam have no place in the management of eclampsia.

Every effort should be made to stabilise the mother (e.g. correct hypoxia, control blood pressure and stop seizures) before undertaking a Caesarean section, as this is a risky procedure to undertake whilst the mother is unstable. Also, the emergency department is a dirty environment therefore the risk of postoperative infection is high. There is unlikely to be diathermy available and the patient may bleed significantly, which is a risk due to the disorders of coagulation that can occur in eclampsia. Furthermore, the baby is only 28/40 and a course of steroid treatment would help lung maturation if delivery were expected to be undertaken. It may be better for the baby to undergo in utero recovery from hypoxia and hypercarbia. If the mother were to arrest in the emergency department then an emergency Caesarean section would be necessary.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Clinical Guideline. Hypertension in pregnancy: the management of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy. August 2010 (revised reprint January 2011)

- Hart E, Coley S. The diagnosis and management of pre-eclampsia. BJA CEPD Rev 2003; 3(2): 38–42.

- The Magpie Trial Collaborative Group. Do women with pre-eclampsia, and their babies, benefit from magnesium sulphate? The Magpie Trial: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2002; 359:1877–90.

- Munro P. Management of eclampsia in the accident and emergency department. J Accid Emerg Med 2000; 17(1):7–11.

20. A Start prostaglandin E2 intravenous infusion and refer to tertiary centre for possible coarctation of the aorta

Stabilisation of critically ill neonates, as with all paediatric patients, should prioritise securing the airway, then establishing breathing and maintaining adequate circulation. Endotracheal intubation and fluid resuscitation are usually required in critically ill neonates and these procedures, if indicated, should not be delayed while waiting for diagnostic evaluation. Establishing optimal ventilation and oxygenation is often sufficient to improve both respiratory and cardiac insufficiency; however, continued IV fluids and resuscitation may be required in the gravely ill neonate. An initial bolus of 10 mL/kg of isotonic fluid (0.9% saline) should be given if necessary. Sepsis is one of the most common causes of critical illness in the neonate and prompt empirical treatment with antibiotics is almost always indicated. If the history and physical examination suggest a possible cardiac diagnosis, a continuous infusion of prostaglandin E2 (Prostin, PGE2, 0.01–0.1 μg/kg/min) should be promptly initiated and paediatric cardiology consulted.

32Coarctation of the aorta is a congenital narrowing of the descending thoracic aorta at or near the connection of the ductus arteriosus. It is the sixth most common congenital heart disease, constituting 8% of heart anomalies. The most dramatic presentation of aortic coarctation occurs in the neonate who is dependent on a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) for blood flow to the distal aorta. After a relatively asymptomatic period of days to weeks, the PDA will close and immediately limit blood flow distal to the coarctation. The ensuing left ventricular failure and systemic hypoperfusion manifest as respiratory distress, cold and pale lower extremities, markedly decreased or absent pulses, metabolic and respiratory acidosis.

- Kim UO, Brousseau DC, Konduri G. Evaluation and management of the critically ill neonate in the emergency department. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med 2008; 9:140–148.

- Landsman IS, Davis PJ. Aortic coarctation: anesthetic considerations. Semin Cardiothor Vasc Anesth 2001; 5:91–97.

21. A IV Hartmann’s at 110 mL/hour. Refer to tertiary centre for further management

Burns are a common cause of injury in children. Most burns occur at home, usually in the kitchen and bathroom. The aetiology changes with age; younger children suffer more scalds, older children more flame burns.

The anaesthetist’s roles include resuscitation, analgesia, sedation, anaesthesia and intensive care management of these patients. Adequate early fluid resuscitation maintains organ perfusion and controls the extent of the burn injury itself. Early excision and covering of non-viable skin reduces morbidity, mortality, and the extent of inflammatory response. Adequate pain management is an obligation and may help to alleviate psychological sequelae.

Resuscitation fluid volumes are calculated using the Parkland formula: for the first 24 hours after the burn, give 4 mL/kg per % body surface area (BSA) burn of crystalloid, half of this volume should be delivered in the first 8 hours post-burn, the other half in the next 16 hours. In this case:

Since 400 mL has already been given in the first 4 hours, only 200 mL should be given in the next 4 hours, i.e. 50 mL/hour.

Maintenance fluid is calculated using the 4/2/1 rule:

- 4 mL/kg/hour for the first 10 kg body weight

- 2 mL/kg/hour for the next 10 kg body weight

- 1 mL/kg/hour for each kg body weight above 20 kg

For this 20 kg child, this works out to 60 mL/hour.